Will the Earth warm by 2°C or 5.5°C? Either way it’s bad, and trying to narrow it down may be a distraction

Climate change is usually discussed in terms of rising temperatures.

But scientists often use a different measure, known as “equilibrium climate sensitivity”. This is defined as the global mean warming caused by a doubling of pre-industrial carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels in the atmosphere.

We use this measure to describe the range of potential temperature increases on longer timescales, and to compare how well climate models reproduce observed warming.

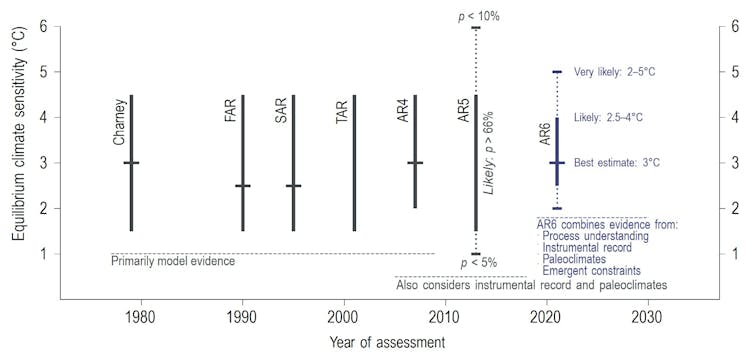

But the predicted range of rising temperature has remained stubbornly wide, somewhere between 2°C and 5.5°C of warming, as assessed in several generations of reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This is despite concerted efforts to narrow it down.

Measuring long-term climate sensitivity is central to future predictions, but we are already seeing the effects of warming across the world with extremes in weather, even at the low end of the range. We argue efforts to boil down Earth’s response to climate change to one number may be unhelpful.

The continued uncertainty could be seen as a failure of climate models to converge on the correct value. Using equilibrium climate sensitivity as a metric for “precisely” predicting the amount of warming expected from a given amount of greenhouse gases is, at best, ambiguous.

History of climate sensitivity

About a century before the first computational estimates of Earth’s climate sensitivity were published in 1967, the Swedish physicist and 1903 Nobel laureate Svante August Arrhenius was the first to estimate values at 4-6°C.

Since the early efforts to model Earth systems, computer simulations have steadily increased in complexity. The first models only simulated the atmosphere, but they have evolved to include vegetation, processes in the ocean and sea ice.

While undoubtedly beneficial to the understanding of fundamental science, each of these added processes has introduced uncertainties in the models’ warming response.

Indeed, given the level of complexity (which differs between models) and resolution of some current models, it is not surprising the estimates of climate sensitivity differ so much.

Self-enforcing feedbacks

Climate feedbacks are central to our argument that equilibrium climate sensitivity is poorly defined. An example of this is the relationship between ice volume and reflectivity.

As highly reflective ice melts on land or sea, the underlying surface is exposed and less sunlight reflected back into space. This increases the amount of warming for a given amount of greenhouse gases. It’s what scientists refer to as a positive feedback loop.

Another such self-enforcing feedback concerns potentially large climate impacts from the release of methane from tropical wetlands and permafrost melt.

Atmosphere models can’t account for this alone, and when they are coupled with an ice-sheet or sea-ice model, the estimate of climate sensitivity changes.

Overheated arguments

It quickly became apparent when studying some recent climate model results that some simulations are producing equilibrium climate sensitivity ranges noticeably higher than before.

In some models, this has been linked to larger self-enhancing cloud feedbacks and how aerosols are represented.

There has been some hesitancy to trust the results produced by these models. They are considered “too hot”.

But we feel these high equilibrium simulations still have value. While we are not arguing they are correct, they force us to consider the what-if situation of very high climate sensitivity, where a doubling of CO₂ would result in warming of 5°C or higher. We know the impact on our environment would be devastating.

Some view high equilibrium climate sensitivity as more consistent with warmer climates in the past, but others have questioned this.

There are several reasons why past climate sensitivity may differ from modern conditions. We may be in a different phase of Earth’s orbital cycles or the balance between volcanism and weathering.

Of course, we should treat all scientific results with caution, but the potential insights gained for uncertain futures are of particular importance when climate change is already being felt across the globe.

Where to from here?

We are continually improving our understanding of the climate – how it has changed in the past and how we think it may change in the future. Equilibrium climate sensitivity has consequently become the single solution we are seeking from climate models, even though the precise value will arguably never be known.

Equilibrium climate sensitivity is undoubtedly a convenient way of distilling future projections. However, it is important not to over-rely on an idealised quantity, because its utility as a useful comparative measure of climate models can give the false impression of a lack of progress in understanding.

There is similarity with the common misconception of a 50% probability of rainfall in a weather forecast, which is often misinterpreted as forecasters not knowing whether it will rain or not.

Communicating uncertainty in projections of future climate conditions is a “wicked” problem. But we risk losing perspective of Earth’s system response by focusing on the effort to make climate models agree on one measure. This is not the answer future generations need.![]()

Jonny Williams, Climate Scientist, University of Reading and Georgia Rose Grant, Postdoctoral Research Assistant in Paleontology, GNS Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.