Jimmy Carter: president, pastor and prophet

An unpopular president, then a respected philanthropist and peacemaker, Jimmy Carter will be remembered as a pious man whose actions were always rooted in his religious faith.

Jimmy Carter, who died at the age of 100, is one of the few former US presidents to have been so celebrated during his lifetime. His remarkable longevity made him the American head of state who lived the longest, was married the longest (76 years) and had the longest post-presidency (42 years). Above all, Carter has made the most of the past four decades, devoting himself to humanitarian action, the peaceful resolution of conflicts, the observation of elections in numerous countries, the defense and advancement of human rights, the eradication of disease and the protection of the environment through his Carter Foundation.

In 2002, he was awarded the ultimate accolade, the Nobel Peace Prize. If the ex-president’s actions have left their mark in the mind of the people, it is hardly because of the four years he spent in the White House – though, recently, some specialists have reassessed his presidency in a more positive light. What is certain is that Jimmy Carter, the only president who was simultaneously an evangelical Christian, a Southern progressive and a center-left Democrat, was an exceptional figure.

Evangelical Christian faith as a common thread

All the actions of James Earl Carter, Jr. must be read in the light of his evangelical Southern Baptist faith, following a personal conversion experience in his forties. In fact, he was the first president in the modern era to speak so openly about his faith.

Running in the 1976 presidential election as a “born-again Christian,” he declared that the most important thing for him was Jesus Christ, and readily referred to his belief in the authority of the Bible as God’s revelation to mankind (biblical inerrancy).

While today white evangelicals (not to be confused with “evangelicals ”, authors of the canonical Gospels) are mainly associated with the right and the Republican Party, this was not the case in the 1970s. This religious movement, barely known to the general public at the time, remained on the fringes of political life and was riven by divisions between fundamentalists and progressives.

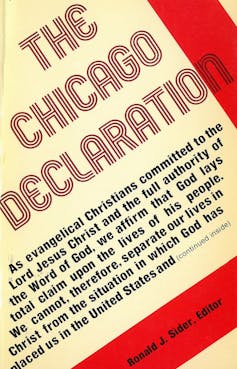

Jimmy Carter, influenced in particular by the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, belonged to the second category. This was in the tradition of 19th-century progressive and socially reformist evangelicalism, which was making a comeback in the 1970s, as illustrated, for example, by the 1973 Chicago Statement on Evangelical Social Concern, calling for the rejection of racism, economic materialism, militarism and sexism.

It is against the backdrop of the post-Vietnam War and Watergate scandals that we must understand the appeal to the American people of a relatively unknown candidate, the governor of a southern state and a peanut farmer, who did not come from the Washington coterie but promised a government that would be “as honest, decent, just, competent, sincere and idealistic as the American people.” On November 2, 1976, he was elected against the incumbent, Republican Gerald Ford, becoming the last Democratic candidate to win a majority of Southern states and a majority of the nation’s counties.

A moralist and visionary president

Candidate Jimmy Carter favored universal health care coverage, proposed cutting military spending and denounced the tax code as “a welfare program for the rich.”

One of his first acts as president was to fulfill one of his most controversial campaign promises: pardon Vietnam War deserters.

Although he flirted with the segregationists during the 1970 Georgia gubernatorial election, he announced, after winning, that “the time for racial discrimination is over” and then took a clear stance against segregation during his term as governor (1971-1975).

As President, he prioritized diversity in his judicial appointments, including Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Amalya Lyle Kearse. His Christian commitment to justice and peace was also reflected in his determination to place human rights at the heart of his foreign policy. His desire for peace in the Middle East led to his greatest success as president: the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt in 1978.

Less well known, but remarkable for the time, was his defense of the environment, which went beyond a simple response to the energy crisis. He imposed fuel efficiency standards on automobiles, created eleven national parks doubling the area protected, signed the Endangered American Wilderness Act (1978), and installed solar panels on the roof of the White House, which were later removed by Ronald Reagan.

Idealism in the face of harsh reality

Equally remarkable is his famous speech on the “crisis of confidence” on July 15, 1979. Known as the “malaise speech,” it was more of a sermon than a political speech, and in hindsight comes across as almost prophetic.

In it, he acknowledges his failures and denounces the crisis of American democracy, the loss of confidence in institutions and materialism, criticizing the excesses of consumer society in almost apocalyptic terms, while reaffirming his faith in the American spirit.

The speech was an initial success, boosting his popularity rating by more than 11 points. Two days later as the elections neared, he ordered the resignation of all members of his Cabinet, then changed his mind and dismissed only five whom he considered ineffective, disloyal or political pushovers. The ensuing confusion and disarray led to his collapse in the polls. Inflation, high unemployment, the energy crisis, and the unresolved American hostage situation in Iran precipitated his downfall.

Between a critical left and opposition from the Christian right

Despite his public profession of faith, Carter firmly believed in the separation of church and state, and that the American government should never show preference for a particular religious faith.

Fundamentalist evangelicals like Jerry Falwell organized political opposition to his policies, which they considered too secular. They allied themselves with Ronald Reagan, even though he was not a very religious man, with whom they shared a fierce anti-communism stance, a desire to limit the power of the federal state, and an opposition to the social changes of modern society, particularly on issues of integration and gender.

Carter also lost the support of the left wing of his party, including some progressive evangelicals who considered his policies too centrist.

An end-of-regime transitional president

Carter’s policies have indeed muddied the waters. On the one hand, he deregulated the banking, oil and transport sectors, opposing the unions in the name of ending monopolies. On the other, he strengthened the state by creating ministries of education and energy, as well as environmental and consumer protection agencies.

In many ways, Carter’s presidency marked the end of the New Deal consensus, in which, for almost 40 years Americans had looked optimistically to the federal government for solutions. He was hated by the right for his loyalty to left-wing ideals, and by the left for his neo-liberal policies. It is against this difficult period of mistrust in the American government that one must read the voters’ turn toward Ronald Reagan’s hopeful promises of a bright, optimistic future for an America that was to be “a shining city on top of a hill”, embodied by a former Hollywood actor who symbolized strength, power and traditional values in a context of economic crisis and distrust of institutions and the government.

Carter’s defeat in 1980 heralded a new political and economic consensus marked by the Reagan revolution. It signaled the end of an aggressive environmental policy that would have terrible consequences and the retreat of progressive evangelicalism in favor of a Christian Right that has since merged with the Republican Party. And ultimately, it foreshadowed the ideological and cultural wars at the heart of American society today.![]()

Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, Spécialiste de la politique américaine, Auteurs historiques The Conversation France

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.